Barstool mysticism

Some of my fondest childhood memories are of visiting my uncle’s bar with my dad, back in the 1980s. Almost every weekend we would stop by Bar Junior — still the name of the place — on our way back from the cinema or the video games parlour. I was fascinated by the deco, which hadn’t changed in almost thirty years, the flurry of faces rushing past the front windows, the crumpled men and women hiding behind newspapers, punters who were there every time we turned up, so that you couldn’t tell whether they were human beings or part of the furniture. As soon as I was old enough I was spending most of my spare time in bars. This is a sports I still practise, even during periods of temperance. For me it isn’t that much about drinking as it is about finding a place where I can plug into the world. Being in London means I spend my time in pubs instead of bars. They might be different animals but they do the work pretty much the same for me.1

What caught my attention the first time I walked into a pub in London was the diversity of the people. Even in a central London boozer you would find persons from all demographics, drinking in the same spot, every now and then having a conversation, sometimes even enjoying their company. This was over twenty-two years ago, when pubs smelled of cigarettes2 and you didn’t have to pawn a kidney to pay for a pint. The pubs where we spend our time these days have changed faster than the city around them, foretelling the shitfication of London. The gastropub fad, first, expelled many from the places they used to call their second home. The craft beer fad, later, finished the job.

I’m not lamenting here the disappearance of an Old London, where everything was nicer and the grass was greener. Times change, yes, and it’d be good for Londoners to start drinking more water, since it doesn’t really make you rusty. But I also can’t help worrying that we are moving towards the eradication of social space in this city,3 and that the death of pubs is part of this process.

The Wetherspoon's Paradox

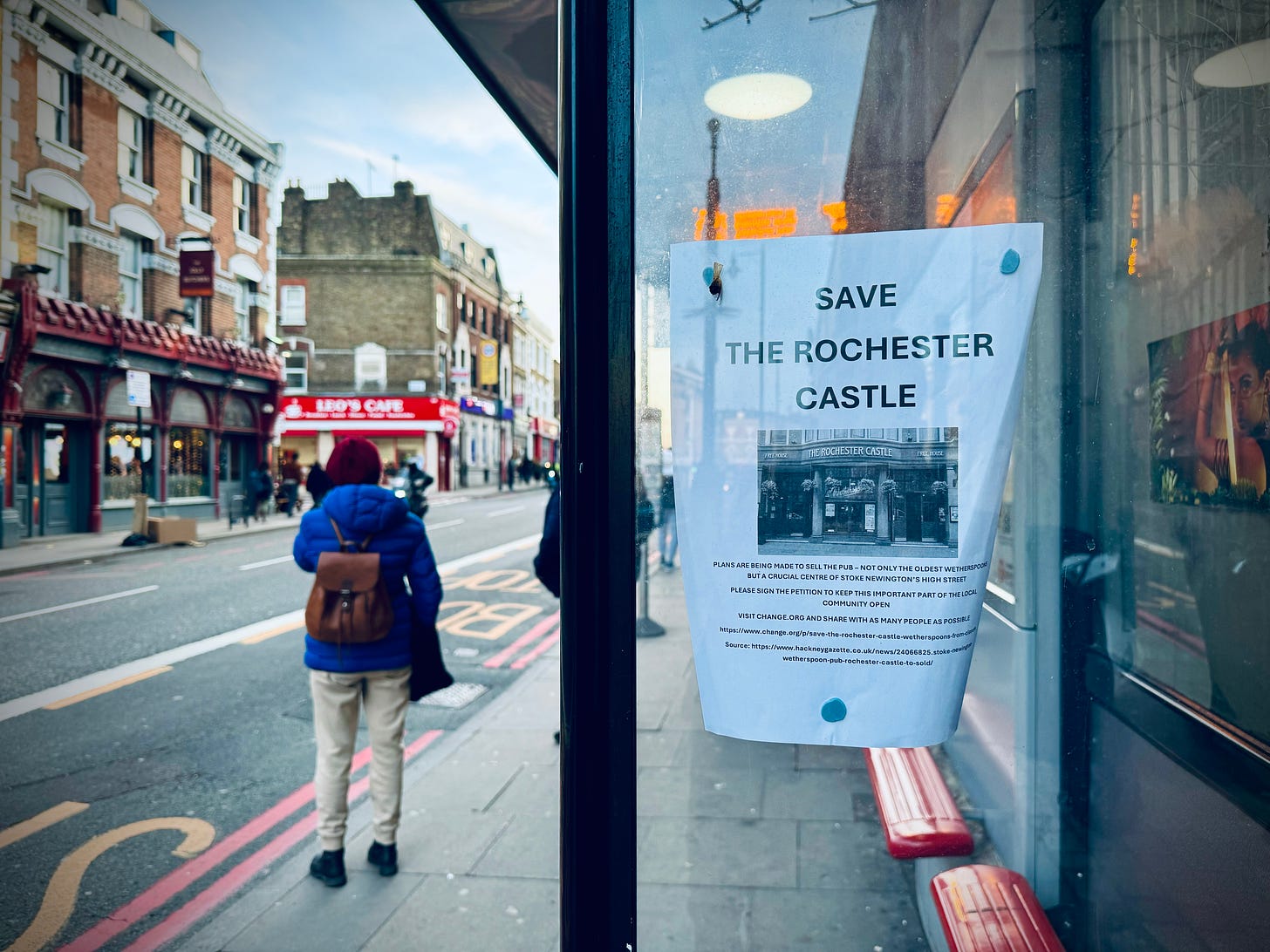

My local, the Rochester Castle, still feels different from the average pub in Stoke Newington, Hackney. Yes, it’s a Wetherspoon,4 and therefore prone to simulacrum, but the current building dates back to the late 19th century, and there’s been a pub in this location in one shape or the other at least since 1702 — this anthropological density contributes to the feeling of being somewhere real. It isn’t pretty, but it’s affordable and inclusive, blessed with an unassuming and friendly atmosphere that perfectly captures the area’s spirit. Old fedora-wearing Jamaicans, posties on a lunch break, noisy families giving drunkards a headache, hipsters on a night out (or still drinking through the morning after), some of the posh neighbours having a furtive fry-up, anyone you might see walking down the high street can be found drinking and eating here. Pub chains are full of contradictions and the one here in question is one of the worst at that. But for all we can say about ‘Spoons, especially about owner Tim Martin’s politics, it was left to a chain once touted to destroy the pub industry to preserve many a London pub, whilst providing an affordable social space for locals. This is something that my friend and erstwhile editor Kit Caless, once a Wetherspoon scholar, rightly defines as “the Wetherspoon’s Paradox”.

The Rochester Castle also has a remarkable musical history. During the punk years of the late 70s and early 80s it was a very busy music venue. There is some dispute over which bands played here, but there's a consensus that at least The Jam and XTC graced the venue in 1977. The version that has the Sex Pistols peddling anarchy in the Rochy at some point in their early days seems to be just a myth, sustained perhaps by the fact that Sid Vicious, bass non-player in the band, used to attend a local school as a teenager. Local legend and librarian Richard Boon —former manager of the Buzzcocks and for some the father of indie music — can often be seen drinking in the pub. His is a presence that links the pub’s present with its past. And not the only one, as some of the locals have been spending time in the building for decades.

The end of social space in the neo(i)liberal city

The Rochester Castle is now up for sale, which is a disheartening turn of events. Most pubs in N16 are prohibitive, and no other venue in the area can provide food, drink, tea and coffee, and heating, all day long, for a few pounds. Whether it’s replaced by another gastro pub, a restaurant, shops, or worst of all, overpriced flats, the sale will kick dozens of people out from the only local place where they can interact with others. The ones most likely to suffer from the pub’s demise — besides the staff — are the dozens of pensioners who hold fort in the Rochy,5 who once evicted will most likely end up drinking alone in their flats, in a city not necessarily known for its inter-neighbour bonds. Last year, WHO declared “loneliness to be a pressing global health threat” — it isn’t surprising, for where are people supposed to meet others, when capital worldwide is doing the best to extract value from every square centimetre, without a second thought for how it might affect individuals?6

It might be naive to think businessmen should care about the impact of their business plans. But it's even more naive to allow businessmen to dictate how, when, and where we come together as social beings — this is where the problem begins. The struggle against the shitfication of cities starts with reclaiming social space for the people.

May the city of the future be an open playground. For now get ready for some lonely times.

EDIT 22.03.2024: Yesterday it was announced that the pub is no longer up for sale.

Spare me the dejection of the shared workspace that is the average London café.

Now, due to the lack of smoke they smell like wet dog and real ale farts.

And everywhere else, I’d say.

The oldest ‘Spoons still open. The chain took it over in 1982.

Especially in the front area, darkly nicknamed “God’s Waiting Room” by the regulars.

I don’t want to fall into conspiranoid thinking and claim that the movement towards urban segregation and loneliness is a carefully planned plot to keep us separated and quiet. But I can’t help thinking it’s part of the neo(i)liberal unconscious and the way this system understands and exploits urban space. Not as social space, but as a space for profit-mining.