“Writing’s a mug’s game,” says Roland Camberton (1921-1965) in his superb Scamp, a novel about a man’s attempts to launch a literary magazine in the London of the late 1940s.

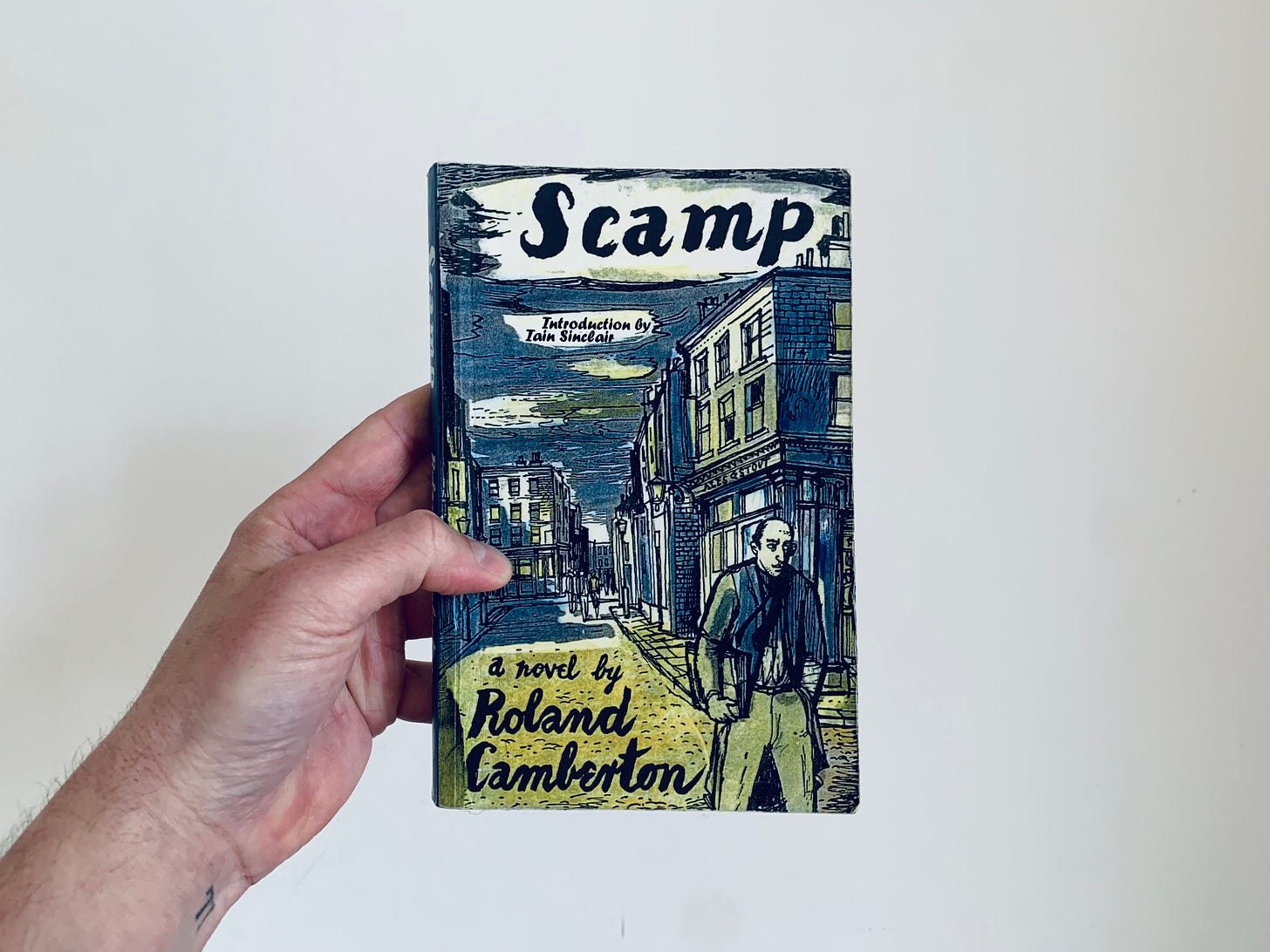

Now, if writing is a mug’s game, I can’t tell you how much of a mug’s game it is to edit a literary magazine, and yet I’d recommend it to anyone who wants to take the métier of inscribing words on a page half-seriously. I’ve been writing for more than a third of my young life and editing a mag for the past ten years. Both occupations are a mug’s game, both are many times thankless, both are perfect money-burning schemes, but only the latter gives you a proper understanding of the literary world from within. More critically: it also teaches you how not to be a spoiled, self-absorbed dickhead — a common character trait among writers, who many times think editors are their butlers and being published is a Human Right protected by the ECHR. I would vote for any political party that made being an editor (at least for a year) a condition sine qua non for publication for any aspiring writer, especially if it is in a magazine run on good will and with no money. But I digress. I don’t want to write about what a bunch of dickheads some of my peers are; I want to write about Camberton’s Scamp — if you haven’t read it you should, as soon as you can get your paws on a copy. The problem is that Scamp is largely out of print. First editions (John Lehmann, 1950) sell in the used book market for anything from a few hundred pounds to well over a grand but occasionally I bump into non-extortionately-priced copies from the 2010 version by New London Editions. And I understand the same press has plans for a new print run, so not everything is lost.

I arrived at Scamp through my pal Gary Budden, a London-lit nerd if there is one. A couple of years ago — during one of the darkest moments of the pandemic — we were naive enough to launch a podcast about London writing. We managed to record a couple of episodes before we started to get requests from writers to talk about their work. Faced with this, which ultimately meant turning a conversation between friends into a chore, we recalled the maxim to “never do anything online or you’ll end up regretting it” and consigned the podcast to history. By then, by the moment we called it off, I had already written to New London Editions to successfully sponge a PDF copy, since I couldn’t find the book for under £100 and I really wanted to talk about it in the podcast without pawning a kidney. I wish I could have honoured my promise, recording an episode about Scamp; thanks for you kindness and sorry, NLE, but writers ruined it for me — I’m sure you can understand. But I digress again, and I ended up writing about how annoying some of my peers are. In my defence, this is also part of what makes Scamp such a good book for anyone who’s enough of a mug like to call themselves a writer, an editor, or a literary adjacent.

“I hope, in fact, to become the editor of a magazine, a highly controversial and at the same time a responsible magazine, in which the views of your party will be given the serious consideration they deserve.”

Scamp follows the misadventures of one Ivan Ginsberg, as he navigates the environs of bohemian late-1940s London, looking to launch the literary magazine that gives the book its title. These are difficult times, WWII is still a very fresh memory, and money and paper don’t come by easily; the fact that Ginsberg earns a precarious living desultorily tutoring Russian to unsuspecting students doesn’t help with his plans. And yet in many ways Ginsberg has quite the life. It was a different geological period when people could live in London1 without surrendering to the Molloch that is Full-time Work — in this Anthropocene of ours there is no space for beatniks. It’s impossible not to envy these group of dropouts as they waste their life away in the watering holes of Soho and Fitzrovia, paying peanuts for their booze and lodging, writing late at night, when their drinking doesn’t demand their presence. Maybe WWIII will see this happens again. One can only hope.

Ginsberg — a stand-in for Camberton — endures in this stinky literary world as well as he can, searching for funding and bylines for his future magazine. This search isn’t very fruitful, since almost everyone is skint, patrons drag their feet, writers are rubbish at meeting deadlines or committing to anything, nobody really cares about literature, and life gets in the way. It’s the same old story, the same old story anyone who’s played the literary game for more than a couple of weeks could tell you. But Camberton tells it better. He tells it with acerbic wit and he tells it with both love and scorn for Soho, Fitzrovia and Bohemia Ltd. Seventy years and more have passed since Scamp and there are aspects about this area of London that remain more or less the same: tourism and gentrification might have largely ruined Soho and Fitzrovia, but scratch a bottle of vodka in any pub shelf here and along will come an intoxicated genie to deliver a monologue that includes a bohemian angle2.

But Camberton doesn’t portray these bums as clueless automata naively swimming in the piss — he shows their decadence but he also shows their slyness: they might deliver a lovable louche rap but being self-centred schemers is their defining attribute — even if they only scheme for pennies. I guess this rings a bell, doesn’t it? Can’t we say the same about the literary bums of today? But I digress: I don’t want to talk about how petty some of my peers are…

“He trailed along behind his sheepish grin from pub to pub, borrowing a few pounds here, publishing a poem there, an amiable, vague inhabitant of bed- sitting-rooms from Chiswick to Swiss Cottage. Everything was forgotten except the simplest needs of survival, fundamental vanity, and money. Above all, money.”

Yes, the vivisection of the literary scene in Scamp is astute and funny and there are several characters that must have been based on real people, so good is the characterisation. There’s one that leaves no doubts, an Angus Stenforth Simms; Simms is clearly based on Julian MacLaren-Ross, a former vacuum-cleaner salesman, renowned both for his books and his alcoholic antics, but more for the latter. There are editors, booksellers, writers without books, painters without paintings, lazy poets, scrubbers, antisemitic Fleet Street hacks, and the rest of the fauna that constitutes literary bohemia. All absolutely sloshed all the time.

I can’t help feeling Camberton — real name Henry Cohen — had one foot in and one foot out of the scene and that’s why he can write with so much sincerity about his peers. His brief oeuvre bears witness to this. Scamp — winner of the Society of Author’s Somerset Maugham Award in 19513 — was followed a year later by Rain on the Pavements, a charming exploration of Jewish life in Hackney in the years leading to WWII. After these two books he disappeared from the scene, dying an unknown in the mid 1960s4. Being Jewish in post war Britain must have been hard — being Jewish and working class must have been a lot harder. And the literary scene — for all its apparent love for perfumed bohemians — tends to expel those who can’t afford to buy a round; being a dropout is one thing — being a dropout and from the lesser classes is a completely different one. This is the same old story too. And these days, for all the self-congratulatory yapping about diversity in literature, class is still the elephant in the room.

“A story a day, that was his minimum task; two thousand words, preferably with a plot, development, a climax, and a twist. After six months of this routine, he was beginning to feel an intense hatred of the short story, in fact, of all writing. What an abominable occupation it was! What a struggle! For what meagre prizes!”

I think of Scamp as I look back at ten years of editing an online literary magazine, my Scamp. I think that overall the experience has been good — most of the people I’ve dealt with were sound, and the ones who weren't I rather forget, since ABH is punished with up to 5 years of actual prison in the UK. Interestingly, unlike for Ginsberg, it wasn’t hard for me to get the magazine started — the hard bit was keeping it alive over time, finding the motivation to keep going. The Digitisation of Everything has make it easier to give birth to these noble projects. There are little excuses not to start a literary mag now. You should start one, everyone should. It costs around £100 a year to keep it running — this is considerably cheaper than therapy5. You won't regret it. Or you might regret it, but you will have learned things in the end.

I wonder what Ginsberg would have done on this day and age. Would he have started an online magazine à la 3:AM Magazine, Minor Literature[s], Catapult, and many others? Or would he have surrendered to the maxim to “never do anything online or you’ll end up regretting it”? The latter, after all, means £100 more a year to spend in pubs. And those £100 should get you at least a pint and a half in Soho or Fitzrovia.

In Zone 1!

How do bums manage to finance their drinking in Central London these days? Some weeks ago I met with a couple of friends from Texas in the Coach and Horses in Soho (the proper one on Greek Street). I ordered three pints of lager and when I went to pay for them with a £20 note the barmaid apologetically said “it’ll be more than that, honey…” Madness.

It seems like a fairy tale, that the SoA would once support something remotely exciting…

For those of you interested to learn more about Roland Camberton, here’s a good article by Iain Sinclair (which also acts as prologue to NLE’s 2010 edition). Unlike much of Sinclair’s writing you won't need a thesaurus for this one.

Sure, if you want to pay authors you’ll need more than this. In Minor Literature[s] editors donate their time, writers donate their writing; no one makes any money. It’s counterintuitive to do things outside of the logic of the market right now, but collaboration is still a thing, and there are many magazines that operate like this. As a plus of this model: it keeps auteurs who like to pretend to live off their writing away from the submissions portal.

Tramps hit SuperRacket booze. Another trick is going round the battle finishing 'The Leftovers' haha, see what I did there! Or unattended drinks of smokers, etc. I once got caught putting a bottle in me coat in the SuperRacket. One night, I halfed a tray of beer out 7-11. Actually, I went on the rampage that night, had untold goodies, including one of them convex mirrors from a car park for some reason I can't remember. Mind you, I had away all sorts them days. Once had a massive candle out a Church. Took it home and chopped into smaller sections and sold them to hippies for £20 a pop. Being a tramp is underrated if you can find a place to put your head down in the cold. I was lucky. Wore out a few friendships kipping people's couches. Broke few flats in Hackney Downs n'all. No water or electric, but a roof none the less. Few nights in the park but mostly in summer. I got away with it for the most part.