Duelling quills

Exploring the tragic feud between The London Magazine and Blackwood's, 1820-1821

And so it begins…

When you can’t write something new you can always tell an old story, and that’s what I’ll do today. I don’t anticipate drawing any conclusions; I don’t want to be clever, or deploy any form of cynical wit. I just think this is a good story, and I’m pretty sure not every knows about it.

That said, you must have heard about the London Magazine. There’s the contemporary London Magazine — a very good literary affair that publishes writers of excellent taste, like yours truly. The mag’s current incarnation can be traced back to 1954, with John Lehmann as founding editor; but the London Magazine “brand” goes back further, all the way to 1732. There have been six different publications with this title in total (1732-1785; 1820-1829; 1840; 1875-1879; 1898-1933; 1954-present) and although publishers past and present would like to claim a continuity between them this isn’t necessarily the case. The events I will recount took place during the second iteration of the magazine, in 1820-1821.

In January 1820, the London Magazine was relaunched after a hiatus of 35 years, with the arch-liberal John Scott as editor1. This revived version was very similar in format to the popular Blackwood’s Magazine (1817-1980), a conservative publication printed in Edinburgh. From the start, John Scott showed a great eye for scouting the key names of his time, providing a literary home to authors like William Wordsworth, Percy Bysshe Shelley, John Keats, and Thomas de Quincey (who later serialised his Confessions of an English Opium Eater in the magazine), among many others. These names might be impressive to us now but they didn’t really impress anyone in the aforementioned Blackwood’s, who marked the London Magazine’s return with a patronising editorial relishing in the similarities between the two publications. This was published in their January 1820 issue:

Notices to Correspondents.

We have much to say to you, gentle Correspondents, but we must devise a new mode of address, now that our Brother-Editor of Baldwin’s London Magazine has adopted our ancient style. Indeed, his Miscellany so resembles our own in form and pressure, that common eyes may, at first sight, mistake it for its elder brother. It is, however, a promising young Publication; and should any part of the reading public be of opinion that it is, in any respect, an improvement upon ours, we must, in like manner, proceed forthwith to exhibit an improvement upon it, till the world will at last have assurance of a Magazine...2

This in turn motivated the following editorial from John Scott in the London Magazine’s February issue of the same year:

We have to thank our brethren Editors of Blackwood for a civil notice in their last Number—just received. This is far more agreeable (to both parties we presume) than a civil war. Not wishing that they should outdo us in courtesy, we make it a point to return their card, and beg to acquaint them, that we shall not willingly allow them to outdo us, in any thing else. If we have (as they say) imitated their manner, have they not, in return, taken some hints from us as to manners? May the interchange continue to be profitable to both!3

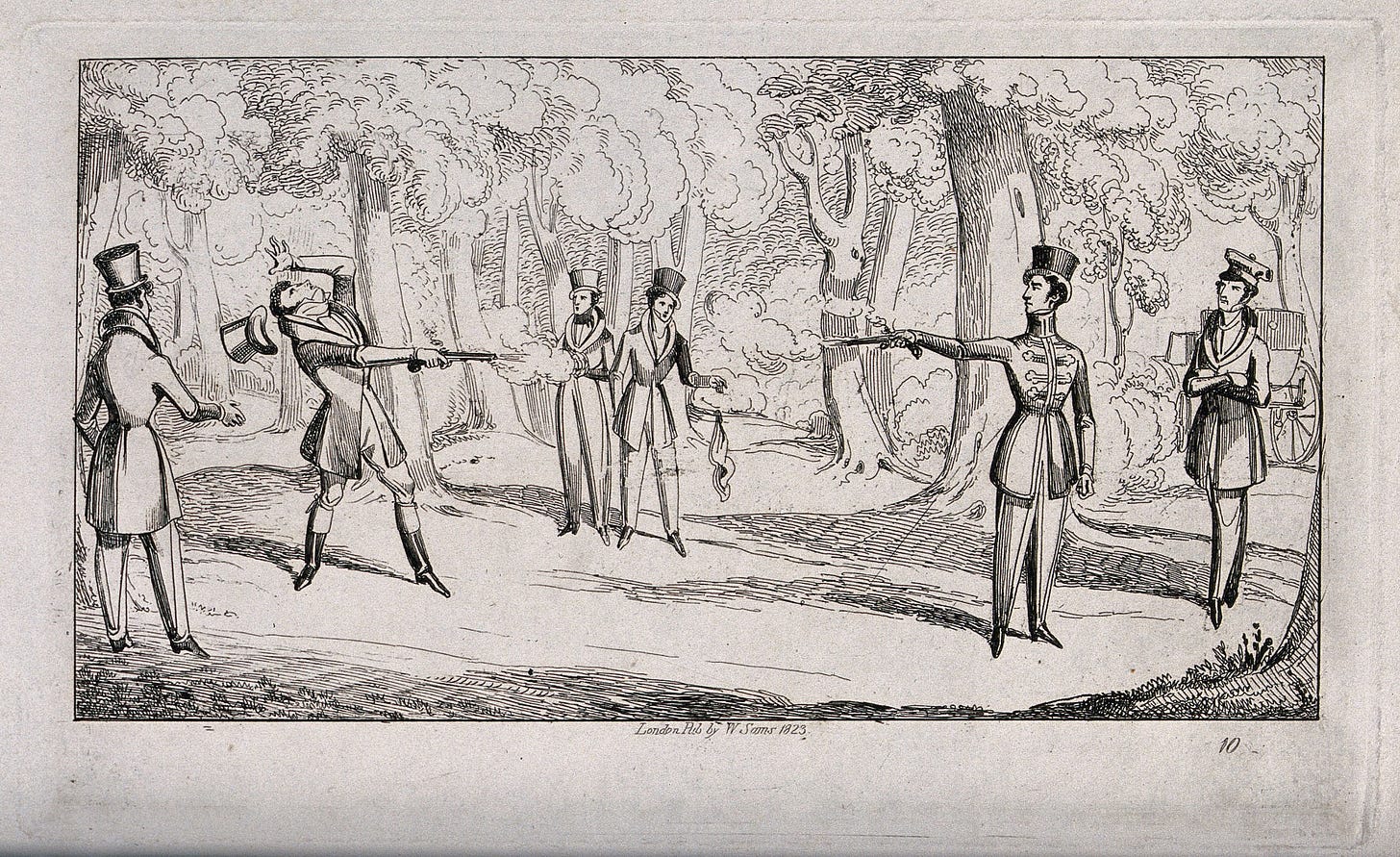

These editorials come across as chummy and friendly, far from “a civil war”. However, a year later one of the editors involved in this insignificant verbal scuffle would be dead, and not killed by irony but after getting shot in a duel.