Decluttering

I suffer from too little shelve space. This is a common problem here in London — a city where leg room comes at a premium. I haven’t counted exactly how many books I can fit in my library but the figure must be in the low hundreds. This means that I need to be selective with the books I keep. I try to prioritise old and first editions, non-fiction and philosophy, and books in Spanish and Italian; there’s some room for books by friends too. I used to keep more books by contemporary indie writers — souvenirs of a literary moment in time and my microscopic contribution to it — but lately I have taken to giving most of these away. This is both to allow these books to reach new readers, and because I find most contemporary writers too irritating to consider giving them a permanent place in my home.

Last week I came to the realisation that at least ten percent of my shelve space was occupied by my to-be-read pile (two piles, to be precise). There were books on these shelves that I had bought in the late naughties, and that I hadn’t got around reading yet. How long should we keep books that year after year we intentionally avoid? I don’t have an answer for this, and as I have written before, I have long felt a thanatic force emanating from these stagnant stash. But this Saturday I woke up full of intent and got rid of at least twenty books that I had either bought on an impulse, or that I had received as gifts and wasn’t interested in reading. This obligatory declutterring felt counterintuitive and disloyal.

Why do I treat books differently to other things? I’ve got no problem at all with getting rid of clothes I haven’t worn in ages, and yet I end up feeling like Judas every time I purge unwanted books.

Duty and guilt

I think much of my relationship with books is determined by a feeling of quasi religious duty towards them. Once a book makes it to my hands — by my own will or unsolicited — I enter into a contractual relationship with it, and not reading it would imply a breach of this contract. This is an unnecessary burden — a fixation either born out of compulsion, or a very Catholic tendency towards experiencing guilt as the default reaction to anything pertaining desire.

I think Jorge Luis Borges hits the nail in the head when he invites us to think of reading as a “form of happiness”.

We should think of reading as a form of happiness, as a form of joy, and I believe that mandatory reading is wrong. It's like talking about mandatory love or mandatory happiness. One should read for the pleasure of [reading] the book. I taught English literature for about twenty years and I always told my students: if a book bores you, leave it. That book wasn’t written for you. But if you read it and the book captivates you, then keep reading it. Mandatory reading is a form of superstition.1

Yes, reading should be an epicurean pleasure, not a chore. For suffering there’s work.2

I hope the books I let go, unopened and full of dust after more than a decade on my shelves, find their ideal, happy readers. Their absence in my to-be-read piles won’t cause me pain any longer.

Until I feel like reading one of them, and I end up buying a used copy online. Possibly one of my own.

Book fetishism

The avid reader I am, I could never get my head around book fetishism.

My unwise, compulsive, guilt-ridden feeling of duty towards books isn’t the same as a fetishistic fixation with them. As I have written before here, I have no problem with establishing hierarchies between books. These red lines are always subjective but they are necessary. Still, the prevalent idea among the Book People3 is that books are a priori good, for the sole reason that they are books and not something else.

This is an idea that is pushed forward mainly by industry grifters, hiding behind the pretence of anti-snobbery and openness. If it is a book, then it automatically deserves our critical respect and admiration, no matter if it’s literary fiction, a romance novel, a memoir, YA, self-help snake oil, the Yellow Pages, the Argos catalogue, or what have you. It all amounts to the same for all books are good. This, from a critical point of view, implies the end of criticism, with critics neglecting all their duties in order to become book marketers. If Borges warns about “mandatory reading” here I would like to warn you about “mandatory respect”.

Interestingly, for all its posing as openness, this uncritical love for books is anchored in a form of pseudo-intellectual snobbery: the idea that books are not only a priori good but also a priori superior to other media. According to this line of thinking, the current desperate state of the world is often the result of people not consuming enough books — “If people read more instead of [insert large list of other activities people do for pleasure] the world would be a better place,” the book fetishist repeats over and over.

Do we need to read just any junk that gets published? Should we self-lobotomise with the thousands of pages of ideological crap that are published day in, day out? Will reading books always make us better? What if we bump into Ayn Rand or a copy of Mein Kampf? Should we treat them with respect?

Second hand information

As someone born in the late 70s I lived a large part of my younger years without the internet. This was great in many ways but it also presented many problems, especially when it came to finding information. As a teenager no information scarcity felt more pressing than the scarcity of pornography.

The pornography of my teens was of the analogical type — by this I mean magazines. We’d get our mags mostly from second hand bookshops, thus giving that “second hand” a new meaning; they would often be at the back of the shop, arranged by title or fetish. Bookshop owners would never ask for an ID, which would probably be frowned upon these vaping days but came handy back then.4 Perhaps in anticipation of the bartering culture that would become popular after the 2001 crisis, you could exchange your magazines in most bookshops too — this is a practice that albeit unhygienic makes me nostalgic for these times of a less pervasive form of capitalism.

It must have been 1996 or 1997 when I was browsing the magazine rack in a bookshop in calle Corrientes, Rosario, when I saw — to my horror — my uni crush walk into the shop. Luckily there was a book table near and I quickly made a move towards it, grabbing the first book at hand. Here she spotted me and got closer; a tense conversation ensued.

“Hey!” — my crush.

“Hey…”

“I didn’t know you shopped here”

“Yes, I do buy my books here every now and then”

“What do you have there?”

“Hmmm,” I looked at the book, “it’s by this guy, Peter Straub…”

“What is it called?”

“Er… It’s called Houses without Doors…”

“What is it about?”

“I’ve got no idea. I’ve just grabbed it. But here it says it’s horror.”

“Oh, I like horror! Are you a horror fan?”

“Not really. But I’ll give it a go anyway.”

Silence.

“OK, then.”

“Right. I better get going.”

“See you.”

I walked to the till and paid for my book. Before leaving the bookshop I saw her walk towards the back and pick up a porn mag. My crush and I never happened but I truly enjoyed Houses without Doors. I recommend it.

Desert island

I like the genius simplicity of “Desert Island Discs”: what eight audio recordings, what luxury item, and what book would you take with you to an island? I would have trouble choosing my audio recordings and luxury item, but I can name my desert island book without a hint of a doubt. That would be Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s Игрокъ (The Gambler).

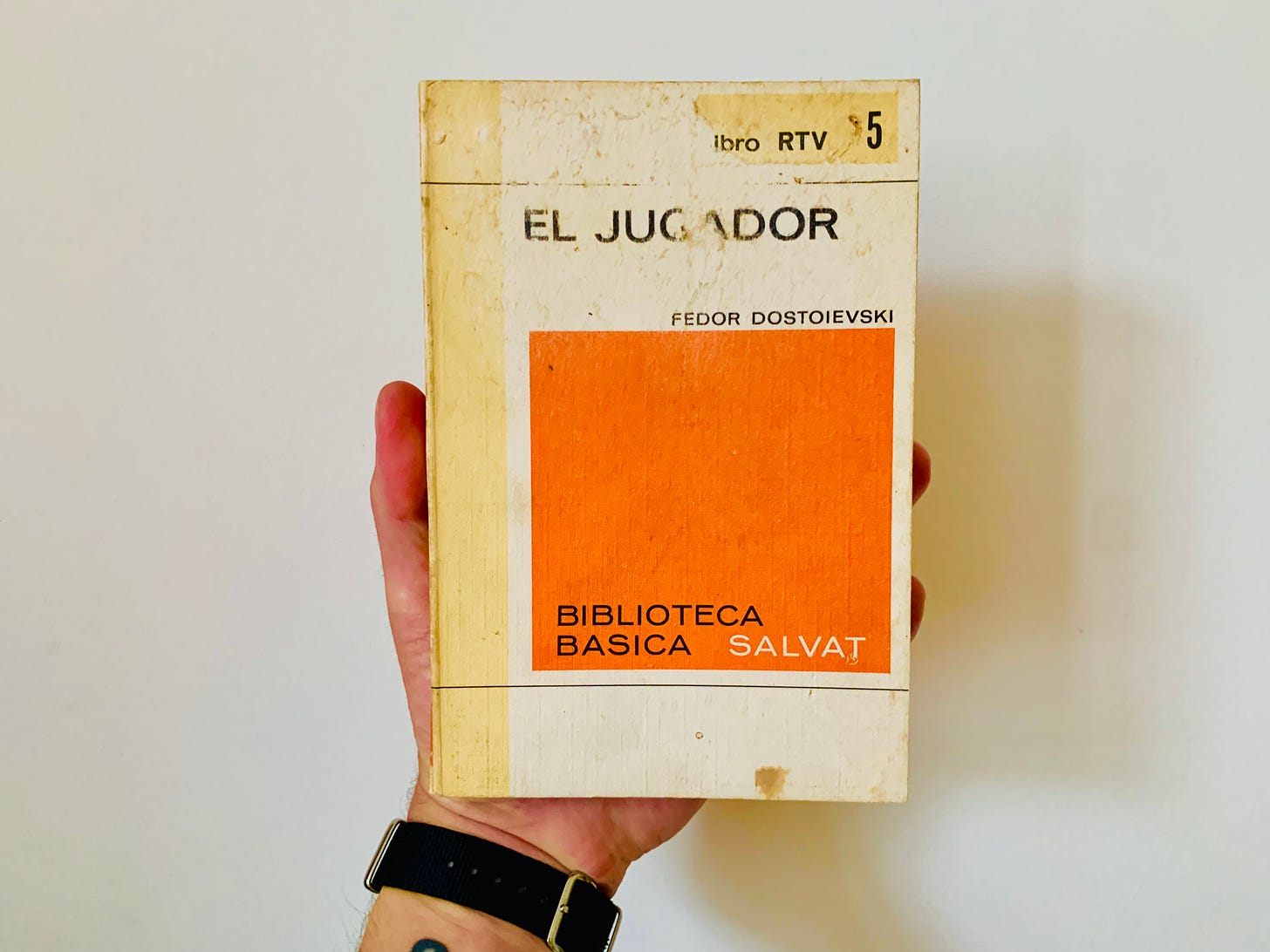

I first encountered this book not among jazz mags but on my mother’s shelves; it was part of the Biblioteca Básica Salvat, a collection of one hundred books, popular in the Spanish-speaking world during the late 60s and early 70s. I picked it up because I liked the minimalist cover; I fell in love straight away with the story, finishing it in one sitting, something I rarely do.

The plot of this short novel revolves around one Alexei Ivanovich — a young tutor for a Russian general’s family. He’s mad about some Polina Alexandrovna, the general’s stepdaughter — a capricious, emotionally-distant and manipulative woman. Alexei slowly becomes entangled in the world of gambling, seeing the acquisition of wealth as a route to earning Polina’s heart. Through this basic plot, Dostoyevsky creates a series of situations that show a great eye for characterisation, even if some of the national stereotypes in the book might come across as a bit dated these days. Игрокъ isn’t considered one of Dostoyevsky’s important works but for me it’s his freshest and liveliest.5 It wouldn’t be Dostoyevsky if the book didn’t deal with guilt and existential angst to some extent, but unlike other works by him here there’s space for humour. I have read it at least ten times in Spanish, five times in English, and now I’m reading it in Italian.

Its ending is perfect in its inconclusiveness. It has influenced many of the things that I have written and that wrap in an unresolved note. You can’t spoil an ending that doesn’t end, so I’ll go ahead and quote it at length. Some background: after experiencing the highs and lows of gambling, love, and his relationships with Polina Alexandrovna and a courtesan named Madame Blanche, Alexei decides to leave Roulettenburg, the fictional spa town where much of the novel takes place. Whether the ending is positive or negative it is open to interpretation:

On the occasion in question I had lost everything — everything; yet, just as I was leaving the Casino, I heard another gulden give a rattle in my pocket! “Perhaps I shall need it for a meal,” I thought to myself; but a hundred paces further on, I changed my mind, and returned. That gulden I staked upon manque — and there is something in the feeling that, though one is alone, and in a foreign land, and far from one’s own home and friends, and ignorant of whence one’s next meal is to come, one is nevertheless staking one’s very last coin! Well, I won the stake, and in twenty minutes had left the Casino with a hundred and seventy gulden in my pocket! That is a fact, and it shows what a last remaining gulden can do... But what if my heart had failed me, or I had shrunk from making up my mind?...

No: tomorrow all shall be ended!6

I can’t say for sure what I like so much about this [non]ending. Is it the idea that one’s luck can change from one moment to the next? Is it the invitation to live dangerously? Is it the reference to being in a foreign land, gambling one’s life away? Is it the Alexei’s weakness, which shows through even in triumph? Is it the ambiguity of that “tomorrow all shall be ended”? I can’t say. Perhaps I keep returning to this book in order to figure this out, just like Alexei keeps returning to the roulette to figure out the meaning of chance.

One thing I know for sure is that I’m glad my mother didn’t think of getting rid of this book to make space on her shelves.

From a conference for PEN Club, New York, 1980. My translation.

I can’t imagine the drudgery of reviewing books for a living, especially books you hate.

The passing reference here is to the characters in Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, who memorise books to preserve their contents in a society where books are banned and burned.

OK, I’ll stop with the puns now.

Dostoevsky wrote the novel in a very short period of time, completing it in just 26 days to meet a deadline imposed by a exploitative publisher. I think this urgency influenced the freshness and pace of the book.

As translated by CJ Hogarth.

We have a pretty good local library (for now). I'd forgotten what a miracle they are, but I feel like a lot of the book world carries on as if they already don't exist. Funny that.

Let me know if you find a solution…